Basketball season is here. Many of you know that my avocation is coaching my daughter Zoe’s basketball team. There are a lot of things that go into coaching: x’s and o’s, psychology of working with high school girls, knowing how to get along with officials (yikes!), and watching film. We watch film to review how we played. We celebrate the things that we did well and we lament the areas that we blew it. Sometimes watching the film is pretty uncomfortable, cringe-worthy even, but in the end, learning from the lows are what improves us as a team.

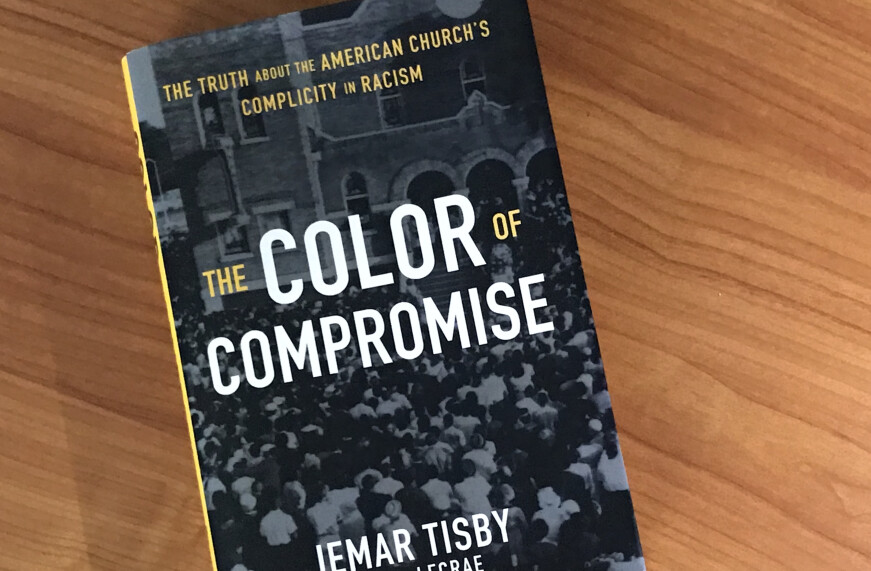

The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism (C of C) by Jemar Tisby is a tough, uncomfortable, cringe-worthy film session that the Christ Church staff undertook to read this past summer. Throughout his book Tisby, a historian/theologian (PCA), recounts events that mark the centuries of our land and how the American Church has dealt with issues of race. This is not an easy task, both for the breadth of history and the characters that he has undertaken to look at. People and situations are complex and need to be handled with care. Tisby speaks to this complexity, “Many individuals throughout American church history exhibited blatant racism, yet they also built orphanages and schools. They deeply loved their families; they showed kindness towards others. And in several prominent instances, avowed racists even changed their minds. (22)” So with this complexity in mind Tisby turns to look at history.

After setting the stage in Chapter 1, chapters 2-10 move from the colonial era, through the revolutionary period, slavery, the civil war, reconstruction, civil rights, right up until Black Lives Matter and the present. Obviously this is a lot of history and much is discussed, for the sake of this review, let me highlight just a few items that stood out. As Evangelicals, we are attuned to the roles that George Whitfield and Jonathan Edwards played in the Great Awakening. We are aware of the power of Whitfield’s preaching and the sublimity of Edwards’ thought. What we do not often reckon with is the fact that both of them were slave owners and true to the complexity of the situation, utilized slaves to provide for various mission endeavors, including Whitfield’s orphanage. Other debates taking place in the early colonial era centered around questions of whether people of color could be baptized and if they were what that meant for their status as “equals” of whites. Compromise was struck with vows like the following: “You declare in the presence of God and before this congregation that you do not ask for holy baptism out of any design to free yourself from the Duty and Obedience you owe to your master while you live, but merely for the good of your soul and to partake of the Grace and Blessings promised to the Members of the Church of Jesus Christ. (sic, 38).

Because of Southern roots Presbyterianism figures prominently in histories of the church and race. R. L. Dabney a prominent Presbyterian minister and theologian was a powerful apologist for the cause of the south. According to Tisby, Dabney advocated a position that not only was slavery morally acceptable, but it was also positive for the African. Quoting Dabney, “was it nothing that this [black] race, morally inferior, should be brought into close relations to a nobler race. (81)” James Henley Thornwell, another prominent Presbyterian, was less overt advocating for slavery but also dodged the question by advocating what he called the “spirituality of the church.” The main idea was that the church had its sphere and its power to assert what the bible teaches, but that it had no responsibility to society and each Christian must exercise their liberty of conscience to choose how to participate in slave practices (85).

From the Civil War, Tisby moves us toward the present with agonizing stops in the reconstruction period. Some of the scenes recounted and practices adapted during this lesser known time of racial history were frankly hard to read. I often wanted to “look away” or “fast forward” through these scenes, but to do so would be dishonest. Chapter 7 focuses on remembering the complicity of the north, especially key for us in the north who can easily villainize our southern counterparts1. After taking a look at the rise of the religious right, Tisby arrives in Ferguson, Charleston and the two most recent Presidential elections, both polarizing in their own rights.

Like watching video and learning from past mistakes, the history that Tisby recounts needs to be looked at and taken seriously as we seek to understand our present times and responsibility with regards to church, race, and image bearers of God. From the beginning Tisby is forthright about his love for the church and his goal “to build up the body of Christ by “speaking the truth in love,” even if that truth comes at the price of pain. (19) As a Black man, Tisby has a perspective that many of us don’t share, but we need to listen carefully to. In addition to being a historian he also has a lived experience that moves him to advocate for the church to learn from past mistakes in order that all God’s people may flourish. Chapter 11 explores ways that the church may go forward in this vein. By nature of looking forward this chapter is less historical and more speculative. Surely not all of the concepts he explores will have universal acclaim, but they are worth considering as they come from a brother in the Lord. The book ends on a hopeful note:

As the American Church considers facing racism, we must remember that God’s command for Joshua to be strong and courageous also came with a promise. “ Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the Lord your God will be with you wherever you go” (Josh 1:9). The guarantee that God’s people can do what God commands is the promise of God’s presence. For Christians God’s promise is a person — Jesus Christ. Immanuel, which means “God with us”, took on flesh to make God’s presence real among us.

So why share all this? Part of the journey that Tisby encourages for the church is education. As a staff each of us felt we learned things through encountering this book that will nuance our interactions as we seek to love all God’s children to the best of our ability. We invite you to take up these pages (available in our library or ask to borrow one of our copies) and think with us how we as Christ Church can live faithfully in GR.

And let me end this film lesson by switching us back to Romans. Yes! We have the presence of the Triune God within us as we live by the Spirit. As we will see this week in vv. 18-25 of Romans 8 though the creation itself is groaning, along with its inhabitants, we move forward, not shrinking from past mistakes but into the glory that is to be revealed to us. Sometimes that glory is hard to see, but who hopes for what he sees? We hope in that which is yet unseen but is certain in Christ.

1 For an even closer look at how issues of race impact northerners take a look at A City Within A City: The Black Freedom Struggle in Grand Rapids, MI by Todd E. Robinson.